VIEW WORKS

Overview

Michael Rees is not an artist who can boast of degrees and diplomas. “I was always drawing as a child – and was particularly good at Mickey Mouse and spaceships – but got an ‘E’ in ‘O’ level art,” he says, deadpan. Attendance at art college did not lead to academic redemption. “I just mucked about, really,” says Rees, urbanely. “I left after a year of a Foundation course. It wasn’t for me.”

Rees had been accepted by Ipswich School of Art in 1979, having grown up in the town. Casting his mind back to his early years, he recalls being “lazy and disruptive” at school, and little better at art college. But albeit that formal education was not for Rees, dropping out of Ipswich School of Art was accompanied by a clear, if paradoxical, decision: to make a life as a professional artist.

Essentially self-taught, Rees now, some 30 years hence, has amply fulfilled his ambition. His work sits off-centre in Cornish art terms – indeed, in many ways, Rees’s paintings have little to do with Cornwall – but it is compelling, intriguing and unique. Again, though, there is a hint of paradox: despite being unquestionably painterly, beneath the surface Rees’s paintings have an abiding literary sensibility, too.

Arriving at the home Michael shares with his wife Tracy – herself a successful artist – the first impression is of books. They are everywhere, neatly (though not alphabetically) arranged on shelves that take up every available space. Tracy is as much a bibliophile as Michael – she always has books and audio book on the go – and a cursory inspection reveals books of the highest quality, from one of Michael’s favourites, the novels of Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard, to works by Paul Auster, Franz Kafka, W G Sebald, Albert Camus and Samuel Beckett. Heavyweights, all – and all forensically devoured by Rees.

Upstairs, in Rees’s studio, the books continue (in fact, they’re even present on shelves aside and above the stairs). There are collections of poetry by Simon Armitage and Seamus Heaney and a no less eclectic music collection, taking in John Cage, Phillip Glass, Frank Zappa, The Fall and Miles Davis. There are DVDs, too. Rees loves film, and says his favourite directors include Ingmar Bergman, Andrei Tarkovsky and Woody Allen. Rees, then, may not have covered himself in academic glory – and he is certainly something of an auto-didact – but he is nobody’s fool. And to look at his paintings is to discern traces of the writers he so admires. If Camus, Beckett and Kafka were preoccupied by existential angst, so too is Rees. If Sebald’s writing is endlessly digressive, and yet always able to produce a coherent, if haunting, theme, so do Rees’s paintings. And in his fidelity to Auster, Rees articulates an abiding concern: “In his memoir, Winter Journal, Auster muses on his life as it moves towards its end. I often worry about the same sort of thing – about the fragility of life and how short our time on earth is.”

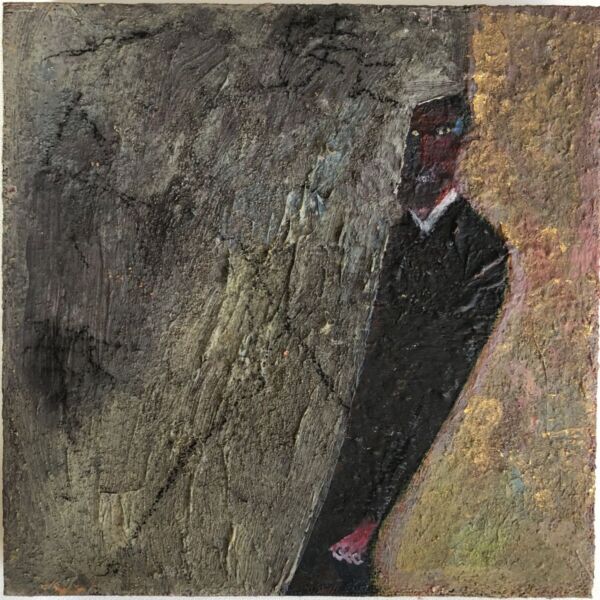

And so to Rees’s paintings. He uses oils, layering them and mixing in wax and fired clay, scraping the surface back with a palette knife time and again until he achieves the right texture. Preferred colours are muted – reds, ochre, grey-white – and often a lone human figure appears, but ill-defined and against a vague, abstracted background. Titles are important – “they come to me when the work is complete, rather than before I start” – and suggest Rees’s themes: ‘Captive’, ‘Enclosure’, ‘The Hostage’ and ‘The Hermit’, for example.

As well as his paintings, Rees’s studio contains a number of small waxwork sculptures. The moulded figures are placed in boxes; the effect is redolent at once of the naive and the macabre. “Art is something I have to do,” says Rees. “It’s what I’ve done ever since leaving art college.” He speaks softly, sensitively, intelligently. Rees is not a man of bombast and bluster, and his oeuvre perhaps reflects an innate diffidence: the figures in his paintings seem as if they are struggling to be heard, to find a voice and a place in the world. Artistic influences include Francis Bacon and Paul Klee (not to mention Alberto Giacometti: “What a genius,” says Rees, “I absolutely love his sculptures and drawings”), but no less formative was Rees’s experience at St Matthews Church of England School in Ipswich, where he was a chorister. His memories of the school are not fond. There is a sense that recollections of strict masters, a vengeful God and fire and brimstone regularly enter Rees’s adult mind, thence to be channelled into his work.

But if all this suggests a tendency for introspection which might emerge as melancholy, Rees in person is light, witty and charming. As Tracy puts it: “He’s not fond of crowds and Private Views, hates paper and plastic take-away cups. He also hates soap operas, hospital dramas, Big Brother and supermarkets. He likes nice teacups and proper tea, as well as good architecture, churches, fine buildings and beautiful landscapes. He doesn’t take

himself too seriously although he is serious about what he does.”

And albeit that Rees’s paintings owe little to Cornwall’s artistic heritage, Cornwall itself – to which Michael and Tracy moved in 1987 – is key to his equilibrium. Rees often goes running and cycling around West Penwith, and is an avid sea swimmer. “He loves the sea,” reveals Tracy. “He needs to be dipped in it for at least 20 minutes a day, preferably more, to feel human.”

Meeting Michael Rees and talking to the man leaves a curious impression. I struggle to think of another artist in Cornwall who is so well read. I can think of other artists whose work goes to a similar kind of darker shore, but so do their personalities. Rees, in contrast, is easy to be with, self-deprecating, amused and amusing. And as much as he worries about life, he enjoys it and has an appetite for it.

No surprise, just before I leave, to find that Rees – artist, sea swimmer, literary man – loves to create music as well. His ‘Noise Nausea’ works can be found at https://soundcloud.com/noise-nausea.

Just as I go, Rees says: “We didn’t talk about God! Well, he doesn’t exist. I found that out in my teens.”

He leaves the sentence hanging, as if it cannot but be ambiguous. The effect, like his paintings, is strangely beautiful.